Freedom, revolt and pubic hair: why Antonioni’s Blow-Up thrills 60 years on

The movie that broke my brain : Blow - Up (1966) By my favourite writer director

Michelangelo Antonioni 😍 #mytop20favouritefilms

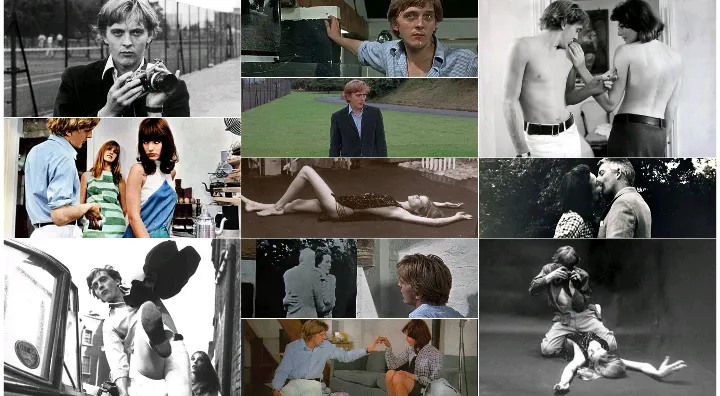

Watching "Blow-Up" once again, I took a few minutes to acclimate myself to the loopy psychedelic colors and the tendency of the hero to use words like "fab" ("Austin Powers" brilliantly lampoons the era). Then I found the spell of the movie settling around me. Antonioni uses the materials of a suspense thriller without the payoff. He places them within a London of heartless fashion photography, groupies, bored rock audiences, languid pot parties, and a hero whose dead soul is roused briefly by a challenge to his craftsmanship.

The movie stars David Hemmings, who became a 1960s icon after this performance as Thomas, a hot young photographer with a Beatles haircut, a Rolls convertible and "birds" hammering on his studio door for a chance to pose and put out for him. The depths of his spiritual hunger are suggested in three brief scenes involving a neighbor (Sarah Miles), who lives with a painter across the way. He looks at her as if she alone could heal his soul (and may have once done so), but she's not available. He spends his days in tightly scheduled photo shoots (the model Verushka plays herself, and there's a group shoot involving grotesque mod fashions), and his nights visiting flophouses to take pictures that might provide a nice contrast in his book of fashion photography.

Thomas wanders into a park and sees, at a distance, a man and a woman. Are they struggling? Playing? Flirting? He snaps a lot of photos. The woman (Vanessa Redgrave) runs after him. She desperately wants the film back. He refuses her. She tracks him to his studio, takes off her shirt, wants to seduce him and steal the film. He sends her away with the wrong roll. Then he blows up his photos, and in the film's brilliantly edited centerpiece, he discovers that he may have...

Michelangelo Antonioni 😍 #mytop20favouritefilms

Watching "Blow-Up" once again, I took a few minutes to acclimate myself to the loopy psychedelic colors and the tendency of the hero to use words like "fab" ("Austin Powers" brilliantly lampoons the era). Then I found the spell of the movie settling around me. Antonioni uses the materials of a suspense thriller without the payoff. He places them within a London of heartless fashion photography, groupies, bored rock audiences, languid pot parties, and a hero whose dead soul is roused briefly by a challenge to his craftsmanship.

The movie stars David Hemmings, who became a 1960s icon after this performance as Thomas, a hot young photographer with a Beatles haircut, a Rolls convertible and "birds" hammering on his studio door for a chance to pose and put out for him. The depths of his spiritual hunger are suggested in three brief scenes involving a neighbor (Sarah Miles), who lives with a painter across the way. He looks at her as if she alone could heal his soul (and may have once done so), but she's not available. He spends his days in tightly scheduled photo shoots (the model Verushka plays herself, and there's a group shoot involving grotesque mod fashions), and his nights visiting flophouses to take pictures that might provide a nice contrast in his book of fashion photography.

Thomas wanders into a park and sees, at a distance, a man and a woman. Are they struggling? Playing? Flirting? He snaps a lot of photos. The woman (Vanessa Redgrave) runs after him. She desperately wants the film back. He refuses her. She tracks him to his studio, takes off her shirt, wants to seduce him and steal the film. He sends her away with the wrong roll. Then he blows up his photos, and in the film's brilliantly edited centerpiece, he discovers that he may have...