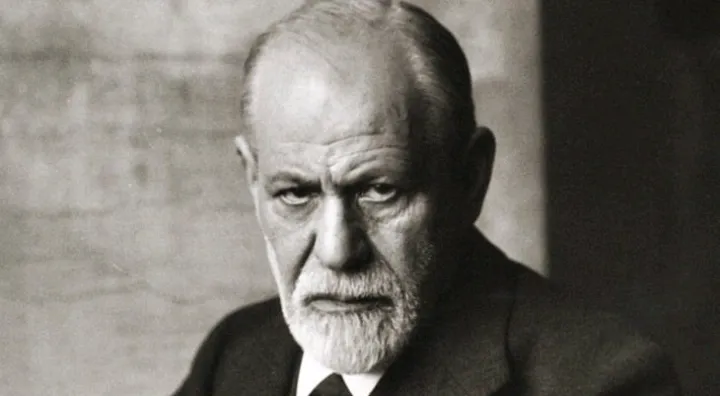

Sigmund Freud

Starting with the study of hysteria in late nineteenth-century Vienna, Freud developed a theory of the mind that has come to dominate modern thought. His notions of the unconscious, of a mind divided against itself, of the meaningfulness of apparently meaningless activity, of the displacement and transference of feelings, of stages of psychosexual development, of the pervasiveness and importance of sexual motivation, as well as of much else, have helped shape modern consciousness. His language (and that of his translators), whether specifying divisions of the mind (e.g., id, ego, and superego), types of disorder (e.g., obsessional neurosis), or the structure of experience (e.g., Oedipus complex, narcissism), has become the language in which we describe and understand ourselves and others. As the poet W. H. Auden wrote on the occasion of Freud’s death, “If often he was wrong and, at times, absurd, / to us he is no more a person / now but a whole climate of opinion / under whom we conduct our different lives …”

Hysteria is a disorder involving organic symptoms with no apparent organic cause. Following early work in neurophysiology, Freud (in collaboration with Josef Breuer) came to the view that “hysterics suffer mainly from reminiscences,” in particular buried memories of traumatic experiences, the strangulated affect of which emerged (in conversion hysteria) in the distorted form of physical symptoms. Treatment involved the recovery of the repressed memories to allow the cathartic discharge or abreaction of the previously displaced and strangulated affect. This provided the background for Freud’s seduction theory, which traced hysterical symptoms to traumatic prepubertal sexual assaults (typically by fathers). But Freud later abandoned the seduction theory because the energy assumptions were problematic (e.g., if the only energy involved was strangulated affect from long-past external trauma, why didn’t the symptom successfully use up that energy and so clear itself up?) and because he came to see that fantasy could have the same effects as memory of actual events: “psychical reality was of more importance than material reality.” What was repressed was not memories, but desires. He came to see the repetition of symptoms as fueled by internal, in particular sexual, energy.

While it is certainly true that Freud saw the working of sexuality almost everywhere, it is not true that he explained everything in terms of sexuality alone. Psychoanalysis is a theory of internal psychic conflict, and conflict requires at least two parties. Despite developments and changes, Freud’s instinct theory was determinedly dualistic from beginning to end – at the beginning, libido versus ego or self-preservative instincts, and at the end Eros versus Thanatos, life against death. Freud’s instinct theory (not to be confused with standard biological notions of hereditary behavior patterns in animals) places instincts on the borderland between the mental and physical and insists that they are internally complex. In particular, the sexual instinct must be understood as made up of components that vary along a number...

Hysteria is a disorder involving organic symptoms with no apparent organic cause. Following early work in neurophysiology, Freud (in collaboration with Josef Breuer) came to the view that “hysterics suffer mainly from reminiscences,” in particular buried memories of traumatic experiences, the strangulated affect of which emerged (in conversion hysteria) in the distorted form of physical symptoms. Treatment involved the recovery of the repressed memories to allow the cathartic discharge or abreaction of the previously displaced and strangulated affect. This provided the background for Freud’s seduction theory, which traced hysterical symptoms to traumatic prepubertal sexual assaults (typically by fathers). But Freud later abandoned the seduction theory because the energy assumptions were problematic (e.g., if the only energy involved was strangulated affect from long-past external trauma, why didn’t the symptom successfully use up that energy and so clear itself up?) and because he came to see that fantasy could have the same effects as memory of actual events: “psychical reality was of more importance than material reality.” What was repressed was not memories, but desires. He came to see the repetition of symptoms as fueled by internal, in particular sexual, energy.

While it is certainly true that Freud saw the working of sexuality almost everywhere, it is not true that he explained everything in terms of sexuality alone. Psychoanalysis is a theory of internal psychic conflict, and conflict requires at least two parties. Despite developments and changes, Freud’s instinct theory was determinedly dualistic from beginning to end – at the beginning, libido versus ego or self-preservative instincts, and at the end Eros versus Thanatos, life against death. Freud’s instinct theory (not to be confused with standard biological notions of hereditary behavior patterns in animals) places instincts on the borderland between the mental and physical and insists that they are internally complex. In particular, the sexual instinct must be understood as made up of components that vary along a number...